Shostakovich 1942 or 1943 (Library of Congress)

Reflections on the Symphonies of Shostakovich

In seeking Shostakovich, I’ve discovered one thing above all: his genius is too often obscured, if not lost altogether, in the babble of commentary that surrounds his work. While an accurate understanding of the historical context is both useful and inspiring, the most important place to look is the one place to which we are often pointed last: his music.

Yet even where his music is concerned, the depth and breadth of his music too often disappears from view. While I have no statistics and can’t confirm this, it seems we are offered in live performance, more than any others among the symphonies, the Seventh and the Fifth. The Fifth appeared in New York classical radio’s WQXR and Q2 2013 year-end Countdown lists, and nothing else. The Fifth, and certainly the Seventh, are not Shostakovich’s greatest symphonies, but they seem to be the ones we’ve come to know best.

But isn’t this a vicious cycle? We’ve come to know them, perhaps moved by the stories that surround them, so we are offered them most often. Then we come to know them even better, so they are, if not comfortable musical companions, at least ones we recognize and feel we understand. But how can the ear expand past these parameters to find the music of Shostakovich that is the most searing, poignant, powerful—and profound—if we are not exposed to other works?

I’m not sure what makes Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, particularly, so popular—more so, say, than the Fifteenth, which is certainly as accessible, or so it seems to me. The Fifth has a great deal to commend it musically, of course. But I find that its strident finale, particularly, diminishes its power.

As for the Seventh, I have to think that, on musical (as opposed to historical) terms, its popularity stems from the so-called “Invasion” theme in the opening movement. The theme repeats, relentlessly; it stays in one’s head long after (years after, forever after) the music stops. I was drawn into and mesmerized by the growing horror of that theme on first hearing. As Shostakovich said, “Idle critics will no doubt reproach me for imitating Ravel’s Bolero. Well, let them, for this is how I hear the war.” [Wilson 173] The Invasion theme continues to move me when I listen to it today, but what I recognize, as I did not back then, is that I’m not listening to the music, but to the history. Beyond that, I wonder how many of us who have had this experience with the Seventh engage with, let alone remember and are affected by, the remainder of the movements to the same extent?

Shostakovich’s Eighth Symphony is another matter, entirely. As I listen, I think, how can I possibly move on from this to other symphonies—or move back? How could I ever want to leave the experience of being inside this music? The answer, for me, is to listen again and again—to try to achieve what Elizabeth so eloquently wrote in a comment in a previous post: “to hear so deeply that the music enters me, and I become it.” I hope some of you will continue to join me on the journey.

The Eighth Symphony: The Context

Shostakovich Working on the Eighth Symphony, 1943

Shostakovich composed the Eighth Symphony in just two months. At the time of its premiere, in November, 1943, Leningrad was still under siege, but “the Soviets had started to repulse the Germans,” and “‘optimistic’ celebration rather than ‘pessimistic’ tragedy was the order of the day.” [Wilson 201]

Laurel Fay observed, “Shostakovich’s failure to limn the psychological climate—to provide an optimistic, even triumphant finale—was a letdown to those inclined to read the symphony, like its predecessor, as an authentic wartime documentary.” [Fay Loc 2018] On its premiere, Shostakovich’s close friend, the polymath Ivan Sollertinsky, while recognizing the Eighth’s superiority to the Seventh Symphony [Fay Loc 2003], wrote, “the music is significantly tougher and more astringent than the Fifth or the Seventh and for that reason it is unlikely to become popular. . .”. [Fay Loc 2009]

Sollertinsky’s remark proved to be prescient. Fay wrote that, “unlike its predecessor, the Eighth Symphony was not immediately taken up and championed by many conductors,” either in the Soviet Union or abroad. [Fay Loc 2032] Worse yet, in February of 1948, the Eighth Symphony, among other works, was banned by decree of the Party’s Central Committee following a series of hearings on charges brought against “deviant artists.” [Taruskin, Oxford 9] On the first day of the hearings, Vladimir Zakharov, artistic director of the Pyatnitsky Folk Chorus [Fay Loc 5517] took the floor to denounce it:

Debate continues among us about whether Shostakovich’s Eighth Symphony is good or bad. In my opinion, the question is meaningless. I reckon that from the people’s point of view, the Eighth Symphony is not a musical work at all, but a “work” that has nothing whatever do to with the art of music. [Taruskin, Oxford 10]

Like Sollertinsky, cellist and conductor Mstislav Rostropovich and pianist Sviatoslav Richter, evaluating the symphony on its merits as opposed to political expedience, believed it to be among Shostakovich’s greatest works. Thirty years later, Richter, in assessing Shostakovich’s music, identified the Eighth Symphony as “the decisive work in [Shostakovich’s] output.” [Wilson 201]

We will give Shostakovich the last word. On December 21, 1949, he wrote to his friend Isaak Glikman:

During my bout of illness, or rather illnesses, I picked up the score of one of my compositions and read it through from beginning to end. I was astounded by its qualities, and thought that I should be proud and happy that I had created such a work. I could hardly believe that it was I who had written it. [Glikman 38]

We can’t know for sure, but Glikman makes a good case for the proposition that Shostakovich was referring to the Eighth Symphony. Glikman observed that “this letter is the first time I know of that he gave such a powerful expression to his belief and pride in himself as a composer.” [Glikman 248, n. 37]

After the ban, the Eighth Symphony wasn’t performed again until 1956. “In 1962, when Jan Krenz conducted the symphony in his presence at the Edinburgh Festival, the composer, overcome, burst into tears . . .”. [Wilson 522]

The Eighth Symphony: The Music

The Eighth Symphony, in C minor, is in five movements, the last three of which are played without pause. The symphony is orchestrated for “4 flutes (3rd and 4th = piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 3 bassoons (3rd = contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, xylophone), and strings.”

The Eighth Symphony, in C minor, is in five movements, the last three of which are played without pause. The symphony is orchestrated for “4 flutes (3rd and 4th = piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 3 bassoons (3rd = contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, tam-tam, tambourine, triangle, xylophone), and strings.”

At approximately seventy minutes, the Eighth Symphony’s length is exceeded only by that of the Seventh. Unlike the Seventh, however, the Eighth presents a compelling musical narrative from the first note to the last. It is not easy to grasp the whole on first hearing, but the whole is evident, and there are no longueurs: every note of it means. When I think of this symphony, words that come to mind include harrowing, poignant, occasionally sardonic, and, above all, profound.

Some commentaries have placed the Eighth, which moves to C major in its finale, in the tradition of other C minor “tragedy to triumph” symphonies, but, as conductor Mark Wigglesworth notes:

There has long been a tradition of C minor symphonies emerging into the major for their optimistic finales. Beethoven’s Fifth, Bruckner’s Eighth and Mahler’s Second all follow the basic plot archetype of tragedy to triumph. But despite the similar tonality it is doubtful whether Shostakovich’s Eighth can be bracketed with these. It certainly travels from darkness to light but it is a journey that yearns more for peace than for victory, and as such its closing bars are far more akin to those of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde.

Yakov Milkis, a violinist with the Leningrad Philharmonic from 1957-1974, told of standing next to Shostakovich on the deck of a ferry from England to France. As they stood, Milkis told Shostakovich that

. . . one of the most remarkable things in the work is the transition to the Finale . . . the music resolves into C major like a ray of sunlight. . . . . Dmitri Dmitriyevich looked at me, and I will never forget the expression of his eyes. “My dear friend, if you only knew how much blood that C major cost me.” [Wilson 356-357]

We cannot know that cost. But we have the symphony, and we can listen to it speak beyond what words can possibly convey.

The Eighth Symphony: Notes on Listening

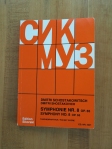

Shostakovich, Eighth Symphony, Edition Sikorski Study Score

For this symphony, I’ve made detailed notes of what my own listening has yielded so far. The notes are included below, with items that may be of particular interest highlighted in bold. (The listening list is at the end of the post.)

How I listened: As a person without technical training, I chose, for a “closer listen,” to focus on shifts in instrumentation, rhythms, and dynamics. (Describing harmonic shifts remains, for me, out of reach.) For this symphony, I purchased a study copy of the score, with which I confirmed what I heard as best I could.

Three note phrases: Shostakovich used simple three-note phrases built on intervals of a major or minor second throughout the symphony. A three-note phrase begins the symphony, and versions of the phrase may be heard quite clearly at the beginnings of the second and fifth movements. The range of musical and emotional moods Shostakovich created with that small element is nothing short of astonishing.

Some General Observations on Orchestration: I marvel at Shostakovich’s use of “unlikely” instruments in solo roles (as Stephen Johnson notes, the piccolo is a notable example) and his use of spare, “chamber music” orchestration. His deep understanding of the complex and nuanced character of his chosen instruments is vividly on display in these passages.

Stephen Johnson’s Discovering Music: For a brief, non-technical introduction to the symphony, try Stephen Johnson’s engaging 20-minute introduction on BBC Radio 3’s Discovering Music here. I found the use of audio examples to illustrate aspects of the symphony particularly helpful.

My Notes, Movement by Movement (Sikorski study score pages and approximate corresponding times in the Rostropovich/LSO Live recording are noted in brackets)

First movement (Adagio-Allegro non troppo)

Some things to listen for: the three-note phrase, the “dancelike” rhythms, and the cor anglais solo at the movement’s close.

At almost thirty minutes, this is the longest movement of the five. Using traditional sonata form (exposition, development, and recapitulation), the movement limns a harrowing musical journey. Throughout the movement—and the symphony as a whole—subtle shifts in orchestral color create motion within the motion of the notes themselves.

The movement begins on an emphatic three-note phrase in the cellos and contrabasses. Second violins and violas stride in, and the upper and lower strings alternate phrases before joining in stately steps to usher in a plaintive theme on first violins. The lower strings subside, leaving the upper strings to rise unanchored [4 1:45], soon joined by flutes and trumpets. The flutes disappear, and cellos and contrabasses re-emerge, though not for long [5 3:10]. A discordant passage, begun on winds alone, signals another shift [6 4:27]. The flutes rise and come to rest on halting rhythms in the strings, a dancelike beat thrown off-kilter by its rendering in 5/4 time, over which the first violins voice a gently rising and falling line [9 5:36]. The rhythm drops out, and the cor anglais takes up the violins’ long-limbed line [10 7:20]. As the cor anglais drops away, the music turns toward a meditation among the first violins, cellos, and contrabasses [11 7:55] before shifting back to the hesitating dancelike rhythms we’d heard before [12 9:50].

The tempo slows on flutes, accompanied by violas [13 10:36]. Little by little, the orchestral texture increases. Cellos join the violas; oboes and clarinets echo and embellish the figures first sounded on the flutes [13 11:10]. The cor anglais joins the flutes on their ascent; the bass clarinet, bassoons, contrabassoon, and contrabasses enter; and, even as the highest notes rise upward, the orchestral color descends into its deepest reach [14 11:55]. The horns lead in the rest of the brass. The timpani sounds, then a marching drum, and the piccolo shrieks [17 12:50]. The urgency of the music continues to increase. The orchestra climbs on a martial beat, drawing back as dissonant horns accompany rising violins [19-20 13:04], soon joined by winds, strings, and other brass, in a relentless surge of notes and sound. To sharp chords on brass and contrabasses, the tempo accelerates, and the rhythm abruptly shifts [33 14:25]. The winds shriek; the density of notes increases; the horns call out. The music ascends, then drops into a relentless march [43 15:38]. A drumroll and timpani issue in two thundering orchestral chords; within them, the brass proclaim a three-note phrase [49-50 16:40]. Brass proclamations issue in three more huge chords, and the chords stop as abruptly as they had begun.

A cor anglais emerges from a haze of strings [52 17:50]. Oboe and clarinet offer brief accompaniment, only to fade away [53 19:56]. The cor anglais finds refuge in a single note, then unfolds to gently dancing rhythms in the strings [53 20:49]. As the cor anglais fades into silence, the first violins and violas wind in spirals above a flowing cello ground [54 21:30]. The upper strings shift to gentle rhythms as cellos and contrabasses voice a deep legato line [55 22:35]. A call on trumpets and horns rises and subsides [56 23:53]. The pulse in the strings slows. The trumpets and horns sound softly as the violins echo phrases we’ve heard before. A lone trumpet sounds a final, receding echo [57 25:52] as the movement ends.

Second movement (Allegretto)

The first movement’s quiet close is shattered by a brash, insistent march. Early on, the piccolos join in, adding shrill sequences of falling notes, echoed on strings and lower register winds and later, with a trace of mockery, on the horns [65-66 1:14]. Yet just as our ears fall securely into step, the strings transform the march into a flowing stream. A piccolo emerges, floating up briefly before whistling over a lightly pointillist ground, joined intermittently on bassoons and contrabassoon and “piccolo” clarinet. [67-71 1:42-2:40] Shifts like these occur in quick succession as the march builds to a seesawing, increasingly frantic climax. We are drawn down from the pinnacle by the xylophone and higher register winds, led by the flutes. [92 5:21] The winds slowly drop out, leaving a solo flute and the contrabassoon. After a brief passage on winds [95 5:56], the strings offer a lyrical passage before the final orchestral blast. The movement closes on the timpani’s emphatic sounding of a three-note phrase.

Third movement (Allegro non troppo)

The third movement opens to incessant motoring rhythms on the violins, as if a Hanon exercise had escaped into the symphonic world. Lower strings punch out single staccato chords. Oboes and clarinets cry out, and trumpets scorch each phrase’s final note. Trombones, tuba, and timpani take up the punctuating blasts begun by the lower strings, a subtle yet emphatic timbral shift. [100 1:35] The strings drop out, and brass and winds drive up the heat. The brass, except the horns, drop out, the strings return, and the rhythmic pattern shifts again: in two note hiccups, it stops and starts [104 2:20]. Another shift, and the strings resume their motoring rhythms, punctuated, now in every measure, on brass and contrabasses [108 2:44]. The urgency and volume continue to increase; a fuller complement of winds and brass interject; the earlier cry of oboes and clarinets becomes a shout [111 3:22]. The orchestration thins out to leave the cellos and contrabasses on their own [113 3:40]. Everything changes, and we are in the midst of an oom-pah band [114 3:51]. Cymbals, bass drum, contrabass, and brass anchor the beat, while trumpets offer up a circuslike tune, punctuated with ascending runs high in the winds. The band fades out, and motoring violins resume with even greater urgency than at the start [122 5:09]. The movement closes on an orchestral crescendo of incessant chords that just as suddenly disappears, and a drumroll augurs what’s to come.

Fourth movement (Largo)

The fourth movement opens on a blast of percussion and huge orchestral chords. The initial clangor dies away as winds and brass lead us downward and drop out to reveal the strings’ deepest sounds. It’s as if we’re lost in Dante’s dark wood, with our only guide a somber passacaglia’s repeating bass. [134 1:09] Solo instruments emerge—a horn [135 5:10], a piccolo [136 6:20], a flute [137 7:03]—only to wander in the dark. A susurrus of flutes yields to a solo clarinet [138 8:05], and clarinets, singly and together on a ground of strings, wend tentatively toward the light. With another, brief susurrus of flutes and ascending notes from the clarinets, the shift from C minor to C major, on which the fifth movement begins, emerges from the dark.

Fifth movement (Allegretto)

Some things to listen for: solo instrument and small ensemble passages, three-note phrases, and possible echoes of the Seventh Symphony’s Invasion theme.

The fifth movement, like the first, though shorter and distinctly different in emotional import, describes a clear narrative arc. Solo passages and spare orchestration yield to a crescendo that culminates in a massive climax, only to subside in a poignant morendo at the movement’s—and symphony’s—close. Throughout, Shostakovich once again demonstrates his nuanced mastery of every instrument in the orchestra—notably those, like the piccolo, bass clarinet, and bassoon, the use of which is too often confined to decoration and comic effects.

A bassoon opens the movement on a three-note phrase with spare interjections from bassoon and contrabassoon. The strings enter on a lyrical sweep that swells briefly and subsides. A lone flute comes dancing in [144 1:39], accompanied on triangle and pizzicato strings, with three-note legato phrases on horn. The flute and strings drop out, and lower register winds and cor anglais enter on a staccato figure over which cellos introduce a long-limbed lyrical line. Oboes enter with a trace of laughter [146 3:03], pushing aside the cellos to offer their own turn at lyricism, punctuated by bassoons. The cor anglais comes in[146 3:33], then all drop out.

The strings enter [147 3:41], soon accompanied by members of the winds and brass, and the music changes course. Staccato figures on trumpet sound out what I hear as an echo of the Seventh Symphony’s Invasion theme [149 4:23-30]. Yet this is not the beginning of a relentless build-up. Instead, the trumpets drop out [150 4:30], and whirling strings and winds, undergirded by guttural humming from bass clarinet and bassoon, lead into what I hear as a round. The cellos and contrabasses [153 5:10] lead off, and the round travels through the strings and winds. Toward the end of the passage, the strings withdraw entirely, leaving an ensemble of winds, initially flutes and oboe, then cor anglais [154 6:00], with bassoon and clarinets entering before the strings return [155 6:50]. As the orchestral texture increases, the three-note phrase with which the movement began becomes ever more insistent. On brass fanfare and timpani [158 7:19], the music gains in urgency and volume, culminating in whirlwinds of notes and huge orchestral chords [168 9:14]. But the music is not leading, as it might have, to a Fifth Symphony-style triumphal close.

Instead, the orchestra withdraws [173 10:29], leaving a lone bass clarinet on a spare string ground [174 10:52]. In this passage, I hear a faded echo of the Invasion theme in the strings [175 11:10]. A violin joins the bass clarinet, and the music shifts into a lithesome waltz [176 11:40] in which a cello’s tender melody [176 11:45] is sneered at by bassoons [177 12:04]. A bassoon offers its reedy voice to the movement’s three-note phrase [177 12:16], joined by delicate accompaniment from xylophone, clarinet, and flute. On gentle strings, the bassoon gives way to a lone piccolo’s delicate melodic fragment [178 13:09]. The strings sing softly on, a flute slips in, and a violin floats upward [180 13:54]. The other violins join and stay aloft on a single chord. The violas pluck out the three-note phrase [180 14:16], and flutes enter tenderly on single notes. The violas join the violins, and the cellos come to rest in harmony with the other strings [181 15:24]. The contrabasses repeat the three-note phrase three times, the third at half the pace [181 15:29]. The strings die away, and the symphony ends.

Listening List

To listen to the Eighth Symphony on Spotify, click here.

On YouTube: Haitink/Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks

In both cases, the conductor is Mstislav Rostropovich. On the Spotify playlist, Rostropovich conducts the London Symphony Orchestra in the recording to which I listened to prepare the post. For David Nice’s complete review of that recording (Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 8 on the LSO Live label, with Mstislav Rostropovich conducting), click here. From the review:

The 16-year-old Rostropovich joined Shostakovich’s composition class at the Moscow Conservatoire in 1943, just before the composer completed his most relentless symphonic tragedy, the Eighth. Rostropovich has since conducted the Eighth many times, and recorded it once before with this orchestra; yet even he must have been amazed and moved by the playing of the LSO at those extraordinary concerts of November 2004.

For previous posts on the Shostakovich Symphonies, click on the following links: Introduction; First Symphony; Second and Third Symphonies; Fourth Symphony; Fifth Symphony; Sixth and Seventh Symphonies

Credits: Quotations may be found at the sources linked in the text, at the page or location shown in brackets. The sources for images used in the post are at the following links: First and second images of Shostakovich, Album cover. The remaining photographs are mine.

There’s really nothing to be added to your essay. You’ve done the research, you’ve listened to the music in as great depth as a professional, evaluated and analysed it; this piece of work (it’s no mere blogpost, particularly when considering the whole of your Shostakovich writings) is amazing in its detail and reference.

Did you say ‘for a person with no technical training? Well, no technically trained person would have been as clear eyed and honest as you. Please, don’t ever get ‘technically trained’.

Friko: Kind words, indeed! And I promise you, in return, that I will not get “technically trained.” (It’s really not an option at this stage, anyway!) David Bloom, the conductor of Contemporaneous, once said to me he sometimes wished he could listen without technically trained ears. At the time, I didn’t understand, but now I do a bit. It does change the way you listen, and what you listen for, I think. I’m enjoying delving into these symphonies, and with the Eighth, particularly, getting some understanding of how it is made, but it’s not essential to enjoyment of the music (and, if fact, if I don’t enjoy the music, then I wouldn’t bother to learn more). I love the way you choose to listen, and the way you describe it here: http://frikosmusings.blogspot.com/2014/02/permutations-cubed.html As I’m croaking along to the Eighth Symphony with my earphones on, I’ll always think of you!

Susan, if you said you weren’t familiar with Beethoven’s op. 132, I can admit without shame, myself, that I don’t know Shostakovich’s 8th. I’ll now listen and look forward to coming back and reading these generous, detailed notes.

Meanwhile, you mentioned our highly opinionated friend Taruskin. I was reminded a few days ago that the Cambridge History of 20th C. Music is available for pre-order this month on

Amazon. I think I’ll be buying it for an alternative view, though it’s really a group of essays by different scholars, so I guess I should say “views.”

editors (from the Cambridge website):

Nicholas Cook, University of Cambridge; Anthony Pople, University of Nottingham

the scholars:

Nicholas Cook, Anthony Pople, Jonathan Stock, Leon Botstein, Christopher Butler, Stephen Banfield, James Lincoln Collier, Susan C. Cook, Peter Franklin, David Nicholls, Joseph Auner, Hermann Danuser, Michael Walter, Derek B. Scott, David Osmond-Smith, Arnold Whittall, Mervyn Cooke, Robynn Stilwell, Richard Toop, Andrew Blake, Alastair Williams, Robert Fink, Dai Griffiths, Martin Scherzinger, Peter Elsdon, Bjrn Heile, Peter Jones

The only scholar I recognize is Leon Botstein, but then I don’t frequent those circles. Robert Fink?

The paperback version $36.00, though if their claim is true that it’s 836 pages, it’s quite the bargain!

Curt: I’ll look forward to your response once you’ve had a chance to listen to the 8th. Interesting to see David N’s response on the Cambridge book–words probably well worth heeding. I’d surely second him on Ivashkin on Schnittke. I picked up a copy of The Schnittke Reader not long ago, and Ivashkin’s opening interview with Schnittke alone was worth the (very modest) price of the book. If you don’t have it already, I think you’d enjoy it, for sure. As for Beethoven 132, there are two maxims in my musical life (life in general, really): first, my knowledge is filled with gaps; second, the more I learn, the less I know. In the latter category, I embarked on my “Seeking Shostakovich” project to get to know Shostakovich’s symphonies. The Eighth was one of many that was totally new to me.

Thanks to David N for saving me $36 on the Cambridge book and to you, Susan, for making sure I read his comment! Given all my Schnittke CDs, reading an interview is almost superfluous, but I shall look it up anyway. Last night I had a long schmooze with Scott Miller, who was impressed when I told him that Schnittke had written for trombone and organ (the piece was worth almost the whole Juilliard series for me). The only performance I found was on an o/p CD, though preserved happily on YouTube. Interested to hear your reactions.

I think you missed the live performance, Susan. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C8EFEQQ5EsI)

Curt: All the better to spend on CDs, eh? Thanks for finding the Schnittke piece you liked so much. You’re right, I wasn’t at that concert, so I missed hearing it then. I do hope you’ll have a listen to Shostakovich’s Eighth. It may not be your sort of music, but I think you’ll recognize its brilliance, at least I hope so!

The Ivashkin Schnittke book I’d most recommend is his little biog published by Phaidon, probably out of print but I picked up an as-new second hand copy. The ‘Reader’ cost me only a fiver in my favourite London remainder/second hand bookshop, Henry Pordes on Charing Cross Road.

I interviewed mighty Alfred, btw, back in Gramophone days, and it was the most impressive meeting I’ve had with any musician. Frail from yet another stroke, answering briefly but trenchantly: the man WAS the music.

Schnittke catered for all, a bit like Martinu (though I don’t know of a Martinu piece for solo trombone). I heard Elliott Carter’s trombone solo piece the other week and there at last (running at about a minute and a half) is a Carter piece I could love.

David: Meant to say thank you for the alert on the Schnittke biog. Would love to read your own Schnittke interview–is it available anywhere? Looks like I will have to check out that Carter piece, too!

Well, Sue, you already know what I think about this being The One, though DDS approaches questions from so many different angles that I couldn’t say it was actually any greater than Four, Ten or Fifteen. The fact that this is your longest piece in the series yet speaks volumes, and of course deeply eloquent ones.

Sure you know my own experience – that the Kondrashin LP of the Eighth was the only Shostakovich in the music room cupboard at my grammar school, so when I heard the Fifth some years later it seemed so disappointing by comparison. Now I can value it for the different order of priorities, but the finale remains a problem.

Just a few observations: I always think of the ‘oom pah’ band tune in the third movement as a Khachaturian parody – the strings even do a divisi Sabre Dance routine – and the massive climax in the finale is a replay of the first movement crisis, with a different resolution. Is the end a retreat into dreams or fairy-tales? I like to think so and that line of Auden’s in my favourite poem, about ‘when stranded monsters gasping lie’ comes to mind.

Slava’s LSO performance was the greatest experience I ever had of the work live. And I’d heard some stunning interpreters: Jarvi, Svetlanov, Berglund.

Sorry to be an eeyore, Mr Barnes, but that Cambridge book looks mighty tedious to go by some of the dreary academic names involved. Taruskin was at least lively and compelling but so biased – a bad influence especially on students, who copy his ideas hook line and sinker. Maybe better to consult the experts on each major voice – ie Calum/Malcolm MacDonald on Schoenberg, Taruskin again and Stravinsky and S Walsh on Stravinsky, Wilson/Fay on Shosatakovich, Adams on Adams (and the music he grew up with) etc. Not to mention my late lamented friend Sasha Ivashkin on Schnittke…

David: I don’t think I did know about that Kondrashin LP. What a wonderful bit of personal music history that is! And how very amazing that the one Shostakovich in your case was not the Fifth or the Seventh.

I’m so glad you included some of your own observations on the Eighth. I always love learning about quotes, parodies, etc., like the Sabre Dance/Khachaturian connection you mention. Stephen Johnson mentioned it, as well, and I thought about including it, but in the end, as an exercise for myself, I opted for seeing what I could glean with my own ears and from the score. By the time I finished, what I recognized most of all was that there was so much more to understand than I could possibly grasp on my own. (This is of course the problem with a self-study, interesting though it is to try.)

It’s easy to get lost in the details, which I know I did, yet at the same time, it was fascinating to be able to get a small hold on how he orchestrated and how he brought out the multi-faceted characters of individual instruments to create musical moods, momentum, effects, and the like. On the “big picture,” your comment and question about the finale’s climax as a “replay of the first movement crisis, with a different resolution. Is the end a retreat into dreams or fairy-tales?” is a wonderful observation. I look forward to listening to the symphony again with that particularly in mind. Something to treasure, that you were able to hear Rostropovich conduct this work live, and I can’t thank you enough for leading me to the recording of that performance.

Your last paragraph did make me laugh, given our previous exchanges about Taruskin, particularly. (Interesting to realize that, in my own little “collection” of books, I’ve got four of the ones you mention.)

David: I have just found the Auden, A Summer Night. How very much it evokes the feeling one gets at the close of the Eighth movement of a momentary respite from what the world is bound to bring. I’m so pleased you noted it, and here, for all, is the poem:

W.H. Auden, “A Summer Night” (June 1933)

Out on the lawn I lie in bed,

Vega conspicuous overhead

In the windless nights of June,

As congregated leaves complete

Their day’s activity; my feet

Point to the rising moon.

Lucky, this point in time and space

Is chosen as my working-place,

Where the sexy airs of summer,

The bathing hours and the bare arms,

The leisured drives through a land of farms

Are good to a newcomer.

Equal with colleagues in a ring

I sit on each calm evening

Enchanted as the flowers

The opening light draws out of hiding

With all its gradual dove-like pleading,

Its logic and its powers:

That later we, though parted then,

May still recall these evenings when

Fear gave his watch no look;

The lion griefs loped from the shade

And on our knees their muzzles laid,

And Death put down his book.

Now north and south and east and west

Those I love lie down to rest;

The moon looks on them all,

The healers and the brilliant talkers,

The eccentrics and the silent walkers,

The dumpy and the tall.

She climbs the European sky,

Churches and power stations lie

Alike among earth’s fixtures:

Into the galleries she peers

And blankly as a butcher stares

Upon the marvelous pictures.

To gravity attentive, she

Can notice nothing here, though we

Whom hunger does not move,

From gardens where we feel secure

Look up and with a sigh endure

The tyrannies of love:

And, gentle, do not care to know,

Where Poland draws her eastern bow,

What violence is done,

Nor ask what doubtful act allows

Our freedom in this English house,

Our picnics in the sun.

Soon, soon, through the dykes of our content

The crumpling flood will force a rent

And, taller than a tree,

Hold sudden death before our eyes

Whose river dreams long hid the size

And vigours of the sea.

But when the waters make retreat

And through the black mud first the wheat

In shy green stalks appears,

When stranded monsters gasping lie,

And sounds of riveting terrify

Their whorled unsubtle ears,

May these delights we dread to lose,

This privacy, need no excuse

But to that strength belong,

As through a child’s rash happy cries

The drowned parental voices rise

In unlamenting song.

After discharges of alarm

All unpredicted let them calm

The pulse of nervous nations,

Forgive the murderer in the glass,

Tough in their patience to surpass

The tigress her swift motions.

Oh, how it gives me a frisson to see its lines here. Unquestionably my favourite poem (though I don’t read enough poetry). One of the fascinations about the first line is that we read it poetically, but at the Downs School, Colwall on the heavenly side of the Malvern Hills where Auden was teaching at the time he wrote this poem, the boys really did take their beds out on to the lawn on perfect summer nights.

As for your choice of books, of course – no dreary academic is ever going to pull the wool over YOUR eyes!

The Kondrashin set was, I think, the first cycle. Primitive sound, idiosyncratic interpretations, but poleaxing. The LP cover, I remember, had – very inappropriately – St Basil’s in the snow on the cover. Oh, and I was so inspired that I ‘wrote’ a piano piece based on the third movement toccata (with Messiaen Turangalila style, F sharp major, in the middle) and won the instrumental class at school playing it. As I never would have done with my limited technical ability on the oboe.

David: What a wonderful piece of “literary history” to go with this wonderful poem (I don’t read enough, either, though it may sometimes seem otherwise). And speaking of “history,” I love your bit of personal history, here–that would have been fun to witness “live.”

I don’t know what I could possibly add. You have ably described the music (in terms I could not do), supplied the primary emotions and flavors of it and topped it off with Auden. I can only feebly say that in my limited experience I have only heard two Shostakovich symphonies live – the 7th and the 8th and of the two I was drawn most (and by far) to the 8th, still am. I find the range of moods astonishing (oops, you said that too!), and even though I couldn’t analyze it I have the sense that every notation of the composition belongs, nothing is wasted – but you said that already too, and better. Here – to your list of adjectives I might add loneliness and anxiety and maybe even some notes of anger or frustration.

Mark: I love your additions to the “adjectives” list. I suspect that, if we all sat down and listed the adjectives that came to mind while listening to this symphony, the whole of the human condition would be represented. It’s interesting to think of the Seventh and the Eighth, both written during the war years, and each massive. Even though I, too, can’t truly analyze how, the Eighth just seems to be perfectly constructed, while the Seventh seems to sag a bit along the way. But, in the end, it’s about the listening, isn’t it? Words fail–except perhaps those like Auden’s! Such a wonderful poem.

(Just as an aside, the two symphonies I’d heard live before I embarked on this project were the Seventh and the Thirteenth. I really feel lucky, this last year, to have had a chance to hear the First, Fourth, and Fifteenth. But not, as yet, the Eighth, alas.)

Fantastic journey you are on here Sue. I wish I had your spirit, and the time, but then again, we are all different and part of the tapestry and therein lies the interest. Technical knowledge, of which I for one have little, must surely bring its own rewards.

I suppose there is an happy innocence in being musically naive, in either exposure or through technical ignorance. Whatever else, all that matters, to me at least, is the pursuit of the (musical) message through whatever suits the individual by virtue of circumstance and desire. One thing is for sure though, you can’t go back.

wanderer: “One thing is for sure though, you can’t go back.” Truer words were never said. As for technical knowledge or lack thereof, the great thing is there are as many ways to listen as there are listeners, and it’s all to the good, “part of the tapestry,” as you say. For myself, while I don’t want to get buried in the details and forget to listen to the whole, I do enjoy learning something of how works I like are constructed, particularly this sort of thing: I was listening to a BBC Radio3 segment on Steve Reich’s The Desert Music today and learned that Reich’s “phasing” had an antecedent in “crosshatching” that Sibelius included in his Sixth Symphony. It reminds me once again of the point David always makes, that there are no bright lines between new and old, and great composers don’t focus on being modern, but rather on making great music (I wish I could find an exact quote, as this is ineptly paraphrased, but hopefully you’ll get the gist).

hmmm…so, perhaps, I should not have started to listen to this after 10pm, telling the pup that we shall go outside in a moment…it is now almost 11 – I’m 40ish minutes in – feeling abit anxious and aggravated by the feel of the music. I will have to revisit this later to read the Auden, and other’s comments, beyond my quick scan. Sue, I wish I had jotted down the name of a composer that was mentioned with Shostakovich in a recent NYT piece – I thought of you… Well, I certainly have not a thing to add, beyond believing that symphonies should have short stories — this piece inspired my mind to escape into a land rather unknown… ~

angela: “symphonies should have short stories”–I do love how your mind thinks. When you return from the “land rather unknown,” I’d love to hear about what you found.

On a different tack, I’m have to say I thought of you more than once tonight at an Australian Chamber Orchestra Concert with Dawn Upshaw which included John Adams’ Selections from John’s Book of Alleged Dreams and Maria Schneider’s Winter Morning Walks (poems Ted Kooser) – names with which I suspect you are familiar.

wanderer: All familiar names–and Upshaw heads up the vocal program at Bard. I’m actually not familiar with this work by Adams, will have to have a listen, nor am I familiar with Schneider’s work–this one garnered three Grammies, though I never know what that’s really worth. How did you like the concert (if you care to say)?

At the risk of coming over all knowally yet again, the title is I think John’s Book of Alleged Dances, and they’re for string quartet – a selection appears on the Earbox set and I adored them all, especially their contrasts and the serious ones. Let’s have a report from wanderer, yes.

David: You know, I missed that entirely: Dreams/Dances! I just read the “Alleged,” and I knew which piece it was–not one I’ve spent time with as yet. I, too, will look forward to wanderer’s report!

‘Dances’ indeed – that was written hurriedly late at night from memory – apologies. Maybe it was wishful thinking.

Give me Dances over Dreams any time!

Thanks so much, Susan, for your blow-by-blow guide, which couldn’t have been better described (and a lot of work, I’m sure!); I used it last night for a second listen to a live recording of Haitink with the Concertgebouw. I think listening to symphonies, in particular, on earphones can put one too much into the music to see the structure and can make a too-passive receptacle of a listener, and your description encouraged more active involvement. So bravo.

Interesting the insights that produced: an appreciation for Shostakovich as a great craftsman: one experiences the journey in greater detail and understands better the brilliance of the means used. Moreover, on the first hearing I missed the sense of peace, or healing, that last movement attains; it had seemed merely to end the work on a “serene” note. Subtle distinction, but significant, I think. Any “happy ending” is hard-won with S., and arguably so, since he had, after all, a front-row seat on the bloody 20th century.

Also, I’m well aware of Shostakovich’s troubles with Soviet officialdom, but I think his environment must have had distinct advantages for his temperament and aesthetics over the avant-gardism of the West. (He was 20 years younger than Webern and Stravinsky, and the same age as Messiaen) I’ve finally acquired wisdom to deal with the conservative/revolutionist scales with equanimity, but that’s another story.

Now on to the 9th!

Curt: You have to know you’ve made my day with the thought that my notes were helpful in the ways you describe. You’re right that it took an enormous effort, particularly as my facility at listening with a score in hand is low, but I’m so glad I did, as it really helped me to achieve a better understanding of Shostakovich’s craft. I like very much your observation on the character of the ending as offering a sense of peace, or healing, as distinguished from “serene.” You’re right, while a subtle difference, it is significant. (I am particularly moved by the close of this symphony.)

Your observation that “his environment must have had distinct advantages for his temperament and aesthetics over the avant-gardism of the West” makes a lot of sense to me. I don’t recall reading that he ever even contemplated emigrating (though perhaps he didn’t have the option). I can’t imagine him as an émigré.

(I know what you mean about listening with headphones, too. I try to avoid it as much as possible, partly for that reason.)

Of all the things that intrigue me here, your comment surely does: “As I listen, I think, how can I possibly move on from this to other symphonies—or move back?”

And then there is Wanderer’s response: “I suppose there is an happy innocence in being musically naive, in either exposure or through technical ignorance… One thing is for sure though, you can’t go back.”

Taken together, the comments bring to mind Paul Ricoeur, the French philosopher whose theories of text interpretation have been so influential. I can’t find anything coherent online and I barely can pull what I learned of his theory out of memory, but this may give you at least a hint of why it seems relevant.

Ricoeur says we come to the world (or a text, or a person) in a state he calls “the first naiveté”. We have certain unquestioned assumptions about what we will experience.

When those assumptions are challenged – perhaps even shown to be untrue – we have two choices: we either return to the first naiveté, or move through the experience of assumption-shattering in order to reach what he calls the “second naiveté”. There, the reality of new experience is incorporated into our view of things and we come to appreciate them with deepened understanding.

As I recall, his position would be that of Wanderer – that we can’t go back. We may refuse to move on, to incorporate what we’ve experienced, but once that first “naiveté” is shattered, the deed is done.

I don’t have any big conclusions to draw here, but it seems to me that if a hermeneutical theory is to have value, it ought to apply to any “text” – including a musical score. And, I keep thinking about the on-going discussion concerning people who say, “I don’t know much about music, but I know what I like.” That could (could, mind you!) be the very voice of the first naiveté speaking, the voice of the person who has yet to allow himself or herself to be confronted by the new, and move through that experience to deeper appreciation.

Well – as I said, I’m way “out there” with this. But I’m intrigued, and I really appreciate this post for the stimulation it’s offered. If I can find the time, I may poke around a bit and see what Ricoeur actually says about text, and whether his theory is expansive enough to include all of the arts.

shoreacres: You may be way “out there,” but I’m certainly glad to follow you to the furthest limb with insights like those you’ve offered here. Particularly in trying this score-reading experiment with the Eighth, I did worry I’d get so mired in the details I’d never get out again–let alone wondering what possible use this would be to anyone else. I consoled myself with the belief that, after stepping back for a while, it would be possible to hear the whole, though now transformed (hopefully to the good). Now, you’ve given to those inchoate thoughts such cogent words: “When those assumptions are challenged – perhaps even shown to be untrue – we have two choices: we either return to the first naiveté, or move through the experience of assumption-shattering in order to reach what he calls the “second naiveté”. There, the reality of new experience is incorporated into our view of things and we come to appreciate them with deepened understanding.”