“My own contempt for the wild & mischievous system of Democracy will not suffer me to believe without positive proof that it can be adopted by any man of sound understanding and historical experience.”

—Edward Gibbon, Letter to John Gillies (24 June 1793)

Early in the chapter “Forms of Government” in his book on the Enlightenment, Ritchie Robertson reminds us: “When thinking about forms of government, or anything else, one has to start from where one is. Enlighteners, looking round eighteenth-century Europe, saw that the prevailing form was monarchy.” [p. 656] It should thus be unsurprising to learn that Enlighteners spent a good bit of time assessing monarchy as a form of government, along with so-called enlightened absolutism. Republics were only slightly on the screen, and democracy even less so.

“To many thoughtful people [Edward Gibbon among them], some version of monarchy seemed not only the commonest but the best form of government.” [p. 657] A “glaring weakness,” however, was the question of succession, which was “(usually) by heredity.” [p. 657] On the one hand, in the absence of an heir, the rule of the Roman Empire “had often been determined by the army, or by a civil war among various claimants.” [p. 657] On the other, “some legitimate heirs had turned out disastrously,” like “Charles VI of France . . . who, after a promising start, was incapacitated by frequent bouts of homicidal madness . . .”. [p. 657]

By the 18th century, skepticism of the divine right of kings had gone by the wayside, and the focus turned toward how to restrain the monarchy. “Enlighteners generally agreed with Montesquieu that intermediate institutions were necessary.” [p. 659] A bit of a bump in the road, however, was that “[a]bsolutist rulers were not keen on having their powers restrained.” [p. 659]

The search was on for checks and balances that might be workable. In England, “the Crown was supported by hereditary nobility in the House of Lords and the people were represented in the Commons. . . . Unfortunately, the practice of English government could not bear very close examination. The Septennial Act of 1716, which required elections every seven years, was often circumvented. Many parliamentary seats were in the gift of powerful noblemen, and patronage, bribery and corruption were standard . . . . As a system of representation, the British government was laughable until 1832 . . .”. [p. 660]

So, what other forms of government might work? “[E]nlightened thinkers made a clear distinction between an absolute ruler restrained by respect for law, and a despotic ruler unrestrained by anything. . . . And yet, could there not be benevolent despots?” Let’s take, for example, “the sequence of Antonines from Hadrian down to the philosopher-king Marcus Aurelius . . . . Gibbon starts his history at the end of this period because it was a happy interlude during which practically nothing happened.” [pp. 661-2] Gibbon did grasp the downside of this: “the Romans paid for their happiness with the sacrifice of their liberty; and . . . since the Roman Empire covered the known world, a subject discontented with despotism had nowhere to flee to.” [p. 662]

The big four enlightened absolutists were Peter I of Russia, Catherine II of Russia, Frederick II of Prussia, and Joseph II of Austria. “All four were astonishing individuals who confirm that personalities are crucial to history.” [p. 663]

Peter I “was determined to Westernize his country. His resolve was strengthened by his visit in 1697-98 to Holland and England, supposedly incognito (though as he was six feet seven inches tall, most people realized who ‘Peter Mikhailov’ was).” [p. 663] He needed access to the sea, and he got it “on the southern shore of the Gulf of Finland,” which also “gave him scope to build a navy, and a site for his new capital, St. Petersburg.” [p. 664]

Reminiscent of Washington, D.C., St. Petersburg was built “on a mosquito-infested swamp . . . . Workers were drafted in at the rate of 30,000, later 40,000 . . . . Huge numbers died . . . . As Russians were reluctant to move to this cold, unhealthy and expensive new site, Peter commanded a thousand officers and bureaucrats to move there and build houses at their own (sometimes crippling) expense.” [p. 664]

While “Peter’s achievement . . . was hugely admired by distant observers . . . . More information generated doubts.” [p. 665] He confined his rival sister, who led “persistent rebellions,” to a convent. [p. 665] He had over a thousand armed guards “executed; some were broken on the wheel and had their corpses hung up outside the windows of Sophia’s convent.” [p. 665]

So, how about Catherine the Great? She was “one of only two women to earn a sculpture in Walhalla . . . “. [p. 666] But “she has divided historians. Some see her as an exceptionally intelligent and dedicated ruler . . . . Others disparage her as an autocrat who only read Enlightenment texts because she was bored during the long northern winters . . . “. [p. 666] “She may well have resembled the fascinating and formidable person created by George Bernard Shaw . . . who controls her rage by admonishing herself: ‘Europe is looking on’ and ‘What would Voltaire say?’” [p. 666]

“Voltaire gave her the most unreserved adulation” but ultimately “realized that in international power politics he was out of his depth.” [p. 668] Voltaire also had a longstanding relationship with Frederick II of Prussia, even to the extent of correcting “the grammar and spelling of Frederick’s French poetry. . . .”. [p. 669] That didn’t work out so well, however. When Voltaire left Prussia with a book of Frederick’s poems in hand, Frederick, “[f]earing that Voltaire would publish the poems, . . . had him arrested . . . until the poems were returned.” [p. 669]

Frederick was a decidedly mixed bag. While “his first act as a ruler was to commission an opera-house, practically his second was to invade the neighbouring Austrian province of Silesia.” [p. 670] In the end, “Frederick . . . illustrates the cardinal weakness of enlightened absolutism as a form of government: ‘because all freedoms under absolutism depended on the will or whim of a single all-powerful individual, any gains made could not be institutionalized, and certainly not entrenched’.” [p. 671]

Joseph II, the last of this fabled quartet of rulers, conceived that “[t]he empire needed to be made into a modern, efficient state on the Prussian model.” [p. 672] An overarching problem “was that the Habsburg Empire was not a state, but a patchwork of ethnically and culturally diverse territories . . .”. [p. 672] So, Joseph figured that, “to reform this polity in line with reason, and to maximize the happiness of its inhabitants, required the determined will of a single man, supported by a slavishly obedient civil service.” [p. 672] He did make a number of significant reforms, particularly in relation to the church, but also to grant greater freedom to serfs “to move about and choose a trade or profession . . .”. [p. 673]

He could, however, “be criticized for micro-management and excessive tidy-mindedness.” [p. 673] “He issued a resolution against making noise in public” including “clapping of hands in the street . . .”. [p. 673] When he learned of a woman who had “acquired a bar of silver of dubious origin, Joseph himself organized a search . . .”. He also ordered his police chief, Count Pergen, to round up the woman’s accomplices. Pergen . . . not to be outdone, held four hearings to establish that one Elisabeth Eberlein had offered for sale some overripe beans, and Joseph commended his zeal.” [p. 674]

Joseph finally wore himself out. Robertson offers the conjecture that “[p]erhaps Joseph’s problem was that, being convinced that truth and reason spoke for themselves, he did not see that he had also to be a politician. He alienated all his potential supporters.” [p. 674] In one instance, his imposition of reforms “led first to tax strikes and then to a full-blown revolt, culminating in 1790 in the proclamation of the United States of Belgium.” [p. 675] He died of tuberculosis “convinced that his project had ended in failure.”

Though “powerful ministers” also took on major reforms, “[t]heir position was highly precarious. . . . if they fell from favour, or if their patron died, they had no powerbase to fall back on.” [p. 675-6] Moreover, “[t]heir reforms generally made them unpopular and, on losing power, they might feel the resentment displaced onto them from an unloved monarch.” [p. 676] Take, for example, the Marquês de Pombal, who, with a free hand in running the Portuguese government “established a system of state education . . . abolished slavery in Portugal (though not in its colonies) . . . . [and] [a]bove all . . . took charge of the reconstruction of Lisbon after the catastrophic 1775 earthquake . . .”. [p. 676] On the death of the king who was his patron, however, “the new ruler, Queen Maria I, a devout woman who hated the sceptic Pombal, dismissed him, and he spent the last five years of his life in rural retirement.” [p. 676]

The quartet of rulers Robertson examines were all “exceptional personalities: dedicated, energetic, single-minded and determined.” [p. 676] They were also “in some respects, damaged personalities.” [p. 677] Peter “developed an antipathy to his son Alexis, who was an invalid and averse to soldiering. When Alexis tried to flee abroad, Peter induced him to return, disinherited him, accused him of conspiracy, had various accomplices tortured to death” and had Alexis “interrogated under torture so severe that he died.” [p. 677] Catherine’s mother treated her daughter very badly, including demonstrating no concern “when young Catherine seemed likely to die of pleurisy.” [p. 677] When Frederick tried to run away “with a fellow-officer (and perhaps lover), Hans Hermann von Katte, they were arrested and brought back to Berlin, where Frederick was made to witness the beheading of Katte from his prison window.” [p. 677] Joseph “had a difficult relationship with his mother [and] both his marriages were unhappy.” [p. 677]

While the “absolutists professed to be the first servants of their people” working for the “common good” . . . . [t]heir people were important not as individuals, but as part of the resources of their states. They always placed the common good above the good of the individual.” [pp. 681-2] Denis Diderot “put his finger on an essential shortcoming of enlightened absolutism: it required unanimity. It assumed that once the clouds of prejudice and superstition had been dispelled, the common good was obvious and undisputable.” [p. 683]

Republics were the third option under Enlightener consideration. There were only a few examples at the time, but “the idea of republicanism carried considerable weight in political discourse, and the ‘virtuous republic’ was a compelling ideal.” [p. 683] A problem, however, “was that not only the medieval but also the ancient republics had all ended badly. They suffered either from internal factional conflict, or imperial overreach, or both.” [p. 683]

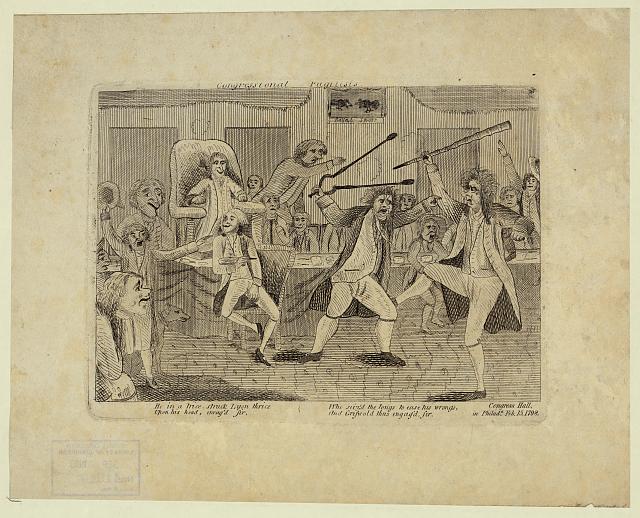

While willing to contemplate republics, Enlighteners thought direct democracies far out of bounds. “Democracy, or rule by the people, is taken to imply constant turbulence, disorder, anarchy and partisan strife, with no larger understanding of the common good. The people are bound to succumb to demagogues, who will either turn into authoritarian rulers, or be swept away by a more determined dictator.” [p. 686]

Gibbon referred to democracy as a “wild & mischievous system . . .”. [p. 686] Baron D’Holbach thought democracy “often makes [their citizens] more anxious about their fate than the subjects of a despot or tyrant.” [p. 686] Immanuel Kant believed that “democracy is necessarily despotic, because those who assume leadership claim to be doing the will of the people, yet the people are in reality never unanimous, so that dissenting opinions are crushed.” [pp. 686-7]

Better, many Enlighteners thought, was a republic, governed not directly by the people, but by their chosen representatives. For Enlighteners, the consensus was they “must be men of property . . . . [i]n present day jargon, they are stakeholders, and powerfully motivated by their own interest.” [p. 687] In the words of John Adams, “very few Men, who have no Property, have any judgment of their own.” [p. 687] D’Holbach agreed: “it is property that makes the citizen.” [p. 687]

Nor were Enlighteners “sympathetic towards arguments for equality . . . . [though] most agreed with the opening proposition of the American Declaration of Independence that ‘all men are created equal’.” [p. 688] They believed, however, that “[a]n attempt to institute political equality, whether corresponding to a fancied natural equality or to compensate for natural inequality, could only be pernicious.” [p. 688]

They squared the circle by determining that, [w]hile it was false to suppose that people were substantively equal . . . it was necessary that they should be formally equal.” [p. 688] John Adams put it this way:

“That all men are born to equal rights is true. Every being has a right to his own, as clear, as moral, as sacred, as any other being has. This is as indubitable as a moral government in the universe. But to teach that all men are born with equal powers and faculties, to equal influence in society, to equal property and advantages through life, is as gross a fraud, as glaring an imposition on the credulity of the people, as ever was practiced by monks, by Druids, by Brahmins, by priests of the immortal Lama, or by the self-styled philosophers of the French Revolution.” [p. 688-9]

There was a lot of concern about factions, too. “In every case, factions stirred up hatreds that led people to place their sectional interest before the good of the country.” [p. 689] As Adam Smith put it: “The animosity of hostile factions, whether civil or ecclesiastical, is often still more furious than that of hostile nations; and their conduct towards one another is often still more atrocious.” [p. 689]

While “a minority view . . . held that factions were preferable to consensus,” “it was commonly thought that republics encouraged factions, which were detrimental to civil liberty.” [pp. 689-90] “This had happened in Sweden’s ‘Age of Liberty’, when unpopular citizens were subject to arbitrary arrest and show trials, and it had happened on a grand scale in ancient Athens . . .”. [p. 690] as Thucydides reported, “[u]nder the rule of demagogues . . . discourse was corrupted, words changed their meaning, and moderation itself invited persecution: ‘Anyone who held violent opinions could always be trusted, and anyone who objected to them became a suspect.’” [p. 690]

“Defenders of classical republican ideals insisted that republics worked so long as their citizens were virtuous.” [p. 690] “Sparta, where the citizens lived on black broth . . . and where money consisted of heavy pieces of iron to minimize commerce by making it inconvenient, was at least virtuous. Farming was thought to be a particularly virtuous activity.” [p. 690] In the words of Thomas Paine, “Commerce diminishes the spirit, both of patriotism and military defence . . .”. [p. 690]

Carried to what sounds like its reductio ad absurdum conclusion, “James Harrington’s Oceana (1656), assumes a society consisting mainly of independent landowners, all prepared to hold public office and to bear arms for their country.” [p. 690] “Certainly,” saith Robertson, “his vision of an agrarian republic cannot be accused of vagueness: his scheme of the government of Oceana is obsessive in its detail. But in most respects Oceana was a dead end.” [p. 691] Among other things, “he wants a balanced constitution that will not only prevent tyranny from above or below but will ensure that nothing can ever change.” [p. 691]

Many Enlighteners discussed the importance of a militia. According to Scotsman Adam Fletcher, “[t]he surest way of limiting factions in a republic . . . was for the republic to be constantly on guard against its enemies.” [p. 692] Niccolo Machiavelli argued that “[s]olidarity among the Romans . . . was preserved by constant wars—wars of aggression, not defence.” [p. 692] There’s a bit of a downside to this, of course: “if the health of a republic depends on aggressive warfare and hence on territorial expansion, it must eventually turn into an empire . . .”. [p. 692]

Enter Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who became the Enlightenment’s “major antagonist.” [p. 692] He won a prize for his 1740s essay in response to the question “Has the progress of the sciences and the arts contributed to the corruption or the purification of morals?” [p. 693] Rousseau responded “with an emphatic assertion that such progress had led to moral corruption.” [p. 693] In his view, in “[s]o-called civilized nations, where the arts and sciences flourish, all fall victim to luxury and vice.” [p. 693] As evidence, “Athens was defeated by Sparta, Rome by the nations that it foolishly despised as barbarians, and the Holy Roman Empire at various times by the Swiss and the Dutch.” [p. 693] Rousseau also posited that “[t]he arts and sciences spring from vices—astronomy from superstition, physics from idle curiosity, eloquence from ambition—and in turn strengthen vice.” [p. 694]

Robertson offers the dead-pan observation, “For this state of affairs, Rousseau naturally has no solution.” [p. 694]

Rousseau followed on with another essay, Discourse on Inequality, which, while “rightly understood as a defence of primitivism, the primitivism it advocates is not the (imaginary and implausible) lifestyle attributed to humanity before history, but a later condition, when humanity had begun to form a society.” [p. 695] Rousseau was all for “[t]he sweetness of family ties” and their “spread to cordial relations with neighbours,” but after that it was pretty much all downhill. [p. 695]

1762 saw the publication of Rousseau’s The Social Contract. By that time, the concept “was a well-established, though controversial, component of political theory. It grows out of the tradition of natural law, whose history goes back to the Stoic ethics developed and popularized by Cicero . . .”. [p. 696] “The Dutch theorist Hugo Grotius maintained that natural law was founded on the Ciceronian ‘right reason’ that man shared with God, and on man’s natural sociability.” [p. 696]

Enter “German lawyer and historian Samuel Pufendorf [who] disagreed . . . . He based his arguments not on theology, but on anthropology: on empirical observations of what human beings were actually like. Observation showed that human nature was not particularly rational or sociable. . . ”. [p. 696] In the world according to Pufendorf:

“It is quite clear that man is an animal extremely desirous of his own preservation, in himself exposed to want, unable to exist without the help of his fellow creatures, fitted in a remarkable way to contribute to the common good, and yet at all time malicious, petulant, and easily irritated, as well as quick and powerful to do injury.” [p. 696]

If Pufendorf is right, how on earth are individuals to be corralled into being governed at all?

Pufendorf posited that, “[t]o enjoy the advantages of society, man has to leave the state of nature and enter the political state.” [p. 697] “[W]riting in Germany soon after the devastating Thirty Years War, [Pufendorf] imagines not a sequence of rational treaties but ‘a series of fear-driven decisions that results in the creation and imposition of a new status or moral person’, i.e. brings the state into being.” [p. 697]

Locke agreed, at least in part. For him, the “’state of nature’ [is one] in which all human beings are equal, without subordination.” [p. 697] “Society . . . originates as a contract, in which the individual cedes some freedom in return for security. If at a later stage that contract is broken—if the government invades the property and liberty of the subject—then the subject is entitled to offer resistance, and, in extreme cases, people are entitled to join together and carry out a revolution.” [p. 697]

“According to Locke, government depends for its legitimacy on the consent of the governed . . .”. [p. 699] But what constitutes consent? For those not in a position to consent directly, Locke came up with the idea of ‘tacit consent’: “I consent tacitly to the laws of a country by living in it . . . . If I travel abroad, I consent to the laws of a foreign government by lodging there.” [p. 699] Well, “[a]s Adam Smith pointed out, you might as well say that, having been carried aboard a ship while asleep, I consent to being there, though with the ocean all round me I have nowhere to go.” [p. 699]

Rousseau seemed to share Locke’s logic, starting “from the fiction of an original contract that men (heads of families) made for the sake of their common self-preservation.” [p. 700] Yet he goes in his own inimitable direction: “He may imagine that his contribution to the common cause is voluntary, and that he can withdraw it while continuing to enjoy the rights of a citizen; but if so, he is wrong, and will discover that the social contract includes the tacit condition ‘that whoever refuses to obey the general will shall be constrained to do so by the entire body: which means nothing other than that he shall be forced to be free’.” [p. 700] Robertson translates, lest we should think this is abhorrent: ‘it means that the individual is required to continue in his status as a citizen, and not to revert to anarchic, pre-social, insecure ‘freedom’.” [p. 700]

Rousseau surveyed the three forms of government in contention and landed on aristocracy. OK, at least he didn’t “mean a hereditary nobility. He meant, rather, rule by . . . the best: citizens will elect as magistrates those fellow-citizens whom they consider the wisest and most upright.” [p. 702] And yet, “[i]t is important to note that Rousseau is not advocating government by representation. Since sovereignty is indivisible, it cannot be divided into the representatives and the represented.” [p. 702] Though Rousseau seemed to like the idea of “popular assemblies,” he didn’t think it “practical for such assemblies to do the work of government. They serve [instead] . . . to forestall any attempt by the magistrates to seize additional power, and to make the people visible to itself.” [p. 703]

Robertson, as is often the case, closes this chapter with keen insights:

“In Rousseau’s social model, people will not always agree, but differences of opinion will cancel one another out and be subsumed under the general will. There are to be no factions. . . . The aim of the state is ‘unity and unanimity’. And in its unanimity Rousseau’s republic becomes a strange mirror-image of absolutist monarchy. As we have seen, the monarch knows what is best for his subjects. In Rousseau’s state, the general will knows best, though as it cannot speak for itself, wise and upright magistrates will give it voice.” [p. 705]

Robertson leaves us with a cliffhanger: “Within a few years, Rousseau’s social model would be tested in practice by the French Revolution.” [p. 705]

To accompany you on your journey here, should you choose to take it, is Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony (1804).

“In May 1804, Napoleon, who had been acceptable to Beethoven as a military dictator as long as he called himself First Consul, had himself crowned Emperor, and the disappointed and angry composer scratched out the words “intitolata Bonaparte” on the title page of his newly completed symphony. So violent was the erasure as to leave a hole in the paper.” [cite]

I love the examples of the loving family values of greatly admired leaders. not to mention the idea that physics is the result of “idle curiosity”.

This is a great and enriching romp as well as an insight into the development of ideas that we

a.) take for granted and

b.) remain with us as controversial.

All so true. And let’s not forget the case of the overripe beans . . . echoed in our times by the case of the chocolate teapot . . .